A Taxonomy of Explosions

A survey of extreme energy and how its transformative power can take us beyond our limits

by Jennifer Boyd

illustrations by Dave Gaskarth

Plucked from its indent in the topsoil, the word ‘explosion’ is slightly warm and covered in dark, perishable spines. Wiped clean and held up to the light, it catches a scattered score of brittle remains, black jet, and kaleidoscopic shards. Its symbolism announces itself in aches and ecstasies: death, violence, celebration, pleasure, birth. Power permeates each exhalation. Explosions speak of and to the apogees of our desires. Due to their ‘anthropomorphic extremism’, explosions can, in a sense, be thought of as our closest living relatives, especially when seen standing on the land, amplified to the ratio of giants. As a result of this conflux of extremes inside the same live specimen, ‘explosion’ is a word that bristles when handled.

In the first instant, before the form of the word collapses on the flat of the palm, we are caused to think of actual explosions: blasts outward, inverting fireballs, smoke columns, burning heat, white tendrils, falling fragments. Secondly come the metaphorical explosions: the rush of thousands of new legs in a ‘population boom’, or the comments and images flung from the centrifuge of a news story. We use them to describe periods of social upheaval and new movements — things that make an impact. Further to this, they inhabit our common phrases: ‘he exploded onto the scene’, ‘they went out with a bang’, ‘she blew my mind’. We also abstract explosions vividly into the body, using their anatomy to lend structure to sensation: the internal shimmering brought on by pleasure, or the wild burn of anger.

Explosions are immensely physical, and yet they are non-material — fire, smoke and sensation are all fleeting. However, they leave behind evidence and residues — explosions lack solids, aside from the ways in which they alter the already-existing. They resound across the body’s interior, the exterior landscape, and the environments created in cultural imaginings.

In the third instant, the first two are found, shaped and held by mediums. Visualisations objectify explosions, generating the ways that we witness them, emphasising and tampering with their physics. In cartoons they are presented as a jagged bang of red, orange and yellow, smoke clearing to reveal still-standing, soot-covered protagonists who have evaded bodily obliteration. Elsewhere, the mushroom clouds of the 1945 atomic bombs were petrified in still photographs, turned into statues and circulated en masse as referent to the singular violence of these events.

We see explosions reflected in the retinas of film stars, pixelated in video game fantasies, and used as status-inducing backdrops in music videos; often they are wasteful energy serving nothing but spectacle and drama. On YouTube you can watch recordings of blasts from warfare still ongoing, and military tests, the camera set close enough that it stands in for the body, knocked to the ground by a shockwave or travelling cloud of dust. Explosions also take place out of sight, unrecorded by the media, and flicker on the screen of the subconscious as a thing always potential. There are places where explosions concentrate, repeating in the same spot again and again. However, they also retain the ability to happen anywhere, at any time, and break new ground.

Explosions are events that can be broken down into four temporal phases. First, there is the build-up: a furtive growth of gas, a camera following a snaking fuse as its increments are eaten by sparks, or the silent accumulation of rage within a body that seems fine on the outside. The temporal framework of this first stage hangs on anticipation, as well as either human decision or natural premeditation. Second, there is the opening ‘split second’ of the explosion which wrenches from nothing to everything quicker than comprehension, followed by a seemingly endless moment of stretch. This phase of shift and stretch is one of flux, in which regulatory constrictions of ticking time and recognisable relationships between things evaporate. In this phase, there is just the body and the explosion.

Third, before the aftermath sets in, there are the ‘loose seconds’ in which realisations begin to drop, falling as if pieces pelting the ground, bringing the witness back round to reality. This phase contains sequential sister blasts, scraps of material licking the blue of the sky, a ringing in your ears, and the sigh of cells. The contrasting silence that follows an explosion can seem like a vacuum, a period when the observer is stunned, before what has happened begins to sink in. A moment of aftershock shock. Fourth, there is the aftermath: eerily precise conical craters, fractured tarmac, and marks on the outer body — either temporary adorations or permanent scars. (Abstract theorisations slip away extraneous at the point at which screams begin to slowly burrow back into our hearing.)

Explosions have two close relations: bombs and eruptions. However, unlike explosions, these signs cannot break from the ways that they are tethered to the solid. Eruptions have an inherent substance, which oozes out following the first rupture. They always have a point of origin; the most prevalent image of an eruption is a volcano, its lava both bubbling out and leading us inside to the Earth’s hot centre. Eruptions do not have the ability to come from nowhere — their sources are solid objects, and their outcome is always material. Dropped, planted in the ground, or strapped to the body, bombs are objects with a specified directive: their rhetoric is connected irrevocably to warfare. That said, an explosion is part of their plan, and as a result, a bomb as the objectification of explosive threat has seen them used as a symbol in artistic practices. For example, in Emily Dickinson’s poem, ‘The Soul has Bandaged Moments’, the line ‘She dances like a Bomb’ takes up the bomb to symbolise the ecstatic soul when in a transient state of freedom from inhibition.

The move into the twenty-first century has seen our relationship to explosions shift, as we drift further from the atomic bombings of 1945. These mushroom clouds hung heavy over citizens of the twentieth century, and now exist as a tinnitus. Our current awareness of nuclear explosions is in relation to secret ownership and maintenance costs, and the repeated rhetoric that if there were to be another nuclear bomb, it would be the end of the world. The foreground of our current soundscape is textured by the IRA bombings of the 1990s, Western drone attacks on the Middle East, and terror attacks on shopping centres and historic sites; the latter, as Paul Virilio and Sylvère Lotringer note in Pure War, are timed to make the evening news in order for them to be repeated and affirmed by a media explosion. States of conflict contextualise any given period of time and they should not be redacted from a taxonomy of explosions. We cannot, and should not, empty explosions of this violent history. However, they are also to be found in other locations. Explosions as a thing and concept should be considered independently from the tangibility and specificity of bombs and eruptions. Examples should be sought from across history, phenomena, literature, film and art, which focus on the explosion as the thing itself. Acknowledging these close relations, but in aim of moving to clear, conceptual terra firma, the defining aspect of any explosion is that it is a sudden, outward expression of energy, in excess of the usual environmental and corporeal levels.

Explosions are both a weapon of dominant masculine history and mascots for its growth fetish. However, to date they have also been used on numerous occasions by anti-authoritarian individuals and groups as a means to talk back to dominant powers in their own language — a means to throw the power found in the explosion back in the face of authority in a turn of the symbolic: for example, by the Suffragettes who blew up London letterboxes in the early 1910s at the service of the women’s liberation movement being heard. (The demarcation between these two sides isn’t stable, and the seduction of the explosive spectacle arguably takes in all who use it. This seduction should be examined critically, but also given into, and twisted for unorthodox uses.)

In the introduction to his 1964 text, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Marshall McLuhan proposes, on explosive terms, that the West has been in a state of expansion up until this point and is now collapsing in on itself:

After three thousand years of explosion, by means of fragmentary and mechanical technologies, the Western world is imploding. During the mechanical ages we had extended our bodies in space. Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned.

Further to this, Jean Baudrillard writes in his essay, ‘The Anorexic Ruins’, that the explosion (the explosion to which McLuhan also refers) has already occurred, and that the only one left is the temporal bomb; however, this has already occurred too, seeing our time thrown into an immobilising, eerie retrogression. Everything feels extreme at this tipping point between explosion and implosion, as we enter the final throes of accelerating towards our limit. Having nearly expanded to our limit globally, it is argued that we know everything, rendering everything dead, and thus anything further is a simulation. Current capitalist culture is based on a deliberate over-saturation as a means to engender exhaustion, and thus limit revolt. There is little undulation in the language used by the government and the media — everything is unrelentingly catastrophic. This constant drama overwhelms and generates retreat, producing a hyper-individualism that allows us to only care for our immediate needs and those close to us, as well as giving rise to an increase in depression, anxiety, illness and breakdown as pressure is internalised.

This permanent state of extreme makes impetus inert. As Paul Hegarty writes in ‘Before and After Baudrillard’ (in his book, Live Theory), ‘The growing density of simulations is destroying it. Implosion is swallowing all the energy of the real.’ However, the idea that everything is simulation, nothing is real, and there is no future, should be moved to the edge of the table, in accordance with Baudrillard’s final assertion in ‘The Anorexic Ruins’ that actually we live in a ‘brilliant epoch’ where ‘no one knows what might happen’. Yet energy has to come from somewhere. With the outward conditions so extreme, a turn inward is inevitable (even if coupled with a simultaneous turn to collective care); perhaps, to this end, rather than a defeated return to the interior, we should instead internalise the explosion. (This, potentially a regrouping, before an explosion back out towards specific targets.)

Commenting on the Challenger space shuttle disaster — in which the shuttle exploded nine miles up into the air seventy-four seconds after take-off, watched at a distance by a crowd of onlookers and televised live — Michel Serres states (in his Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time with Bruno Latour) that these disasters cause us to look high up into the sky: ‘This object, which we thought simply brought us into a relationship with the stars, also brings us into relationships among ourselves’. The live broadcast cuts between the crowd of onlookers and the shuttle going up, then between the onlookers and the exploded and falling shuttle. A simultaneous coming down from euphoria that was rendered unreal following weeks of build-up towards what they fully expected to happen but then didn’t. A collective realisation done out in the open as each of their faces looked down and then once again upturned. Explosions are shared things; according to Serres, these events are the statues that give us light and shadow allowing us to analyse our science and our selves, rather than dying cold in the bright light of the pure sun.

As Baudrillard writes: ‘it has become apparent that growth has ended and that we have entered a field whose consequences are unpredictable’; currently, we’re at the edge of expansion and have hit a wall — when everything is known, nothing means anything, and simultaneously anything feels possible as, upon hitting this wall, mandates dissolve. Further to this, Baudrillard writes, ‘what is worse — bordering more on a catastrophe than a crisis — is when the system overextends itself, when it has already left its own goals behind and thereby no longer has any remedies at hand’. Explosions are a motif whose potency has endured — we cannot seem to stay away from them. The physicality of explosions is so strong that their gesture reaches us, transcending page and screen in a molecular-to-molecular relation — the stirring they do to the land speaks to the stirring they do of our bodies, even at degrees of removal. They offer something that feels definite in an increasingly nebulous time.

The core intention for creating a taxonomy of explosions is to take stock of pre-existing explosions at this specific moment, as an exercise to examine their qualities, how we use them, and seek possible revolutionary uses that are not limited to mimicked retaliative blasts and traditional forms of direct action. Specifically, within this preliminary shrapnel, the focus will be on temporality and materiality — on the understanding that they are two things currently in states of disquiet — and interior to exterior relations, and how both sites might stand to be transformed.

To generate principal taxonomy categories, three inceptive images can be turned to. The first is the upward bloom of an actual explosion. The second is a spherical bang, which produces a perverse symmetry of parts outward from a dense centre. The third is one that cannot be seen: it is an abstract sensation based in organic cells.

Principal categories: Bloom, Bang, Bodily

Subcategories: animal, anti-authoritarian, astronomical, conspiracy, girlish, heat, liberating, light, linguistic, man-made, multiplied, mythology, pleasure, pseudo-science, sonic, symbol-shattering, women

Explosions punctuate the line of history. Although each explosion has its own specifics and there are numerous types of actual explosion (chemical, nuclear, natural, astronomical, etc.), their images persist in their near sameness which means that when we look at one, we are simultaneously looking at every explosion that has ever occurred — a concertina of temporality is folded inside each one. The resulting paradox is that we are staring at a thing that contains the past and yet we are resolutely in the present moment.

How do you study a thing that is multiplex in its symbolism, territory, temporality and materiality; a thing that is not solid or single in place; a thing that is duplicitous in its seductions? Looking at the bright bursts of explosions on the horizon line of our trajectory causes a contraction between times, places and disciplines, in which actual explosions are mixed with cultural imaginings, and there is the possibility for popular culture to be classified next to grand historicised events. Explosions are a lens that can be used to create a kind of queer, alternate history based on extreme energy. Due to this contraction, rather than writing a timeline of explosions, a taxonomy based on thematic classification can instead provide a framework for excavation. The aim: to create an active resource for theorisation as well as a resource of extreme energy — a box of explosives that we can look down into. Crack the lid open and watch them fizzing. The preliminary shrapnel of this taxonomy is lined up in size order, moving from the grand macro down into the cellular micro. These first fragments stand as field notes on a small number of examples, written accordingly as analysis, description and ‘off-record’ speculations.

Clarice Lispector used her own childhood experiences as reference for her character Macabéa in The Hour of the Star

Fragment 1

A large boulder, effervescent when touched.

In the final book written before her death, The Hour of the Star [Bodily: astronomical, girlish, linguistic], Clarice Lispector inserts explosions into her text. They occur (explosion) with an affective lack of warning, sounding out eight times from the book’s interior. Wedged into the thick flesh of sentences, the brackets around them mirror an explosion’s outer energy ring. These explosions punctuate the lifeline of Macabéa, a sickly girl who lives on Coca-Cola and hot dogs in the slums of Rio. The textural body can be taken as proxy for the body of Macabéa — these explosions do not belong to the external landscape of the narrative, rather, their impact is inside her. Their jangling accrual articulates the dislocated build of Macabéa’s form as if a skeleton of pressure points.

In The Impossible, Georges Bataille writes, ‘nothing exists that doesn’t have this senseless sense — common to flames, dreams, uncontrollable laughter — in those moments when consumption accelerates beyond the desire to endure’. Akin to Bataille’s understandings, Macabéa’s explosions sound after things that are the inverse of societally upheld achievements: when she loses her job; when a relationship ends; minutes of irrepressible giggles. In the text there are numerous points at which Macabéa’s pallid frame and face are focused on, but despite this, her image is never fully stuck down, and frustratingly for her love interest, she continues to feel free despite the abject nature of her circumstances. Macabéa prides herself on being perversely spectacular in the plainness and meaninglessness of her life — Bataille writes, ‘but the desire for existence thus dissipated into night turns to an object of ecstasy’. The explosions mount a contrary prophecy, markers of Macabéa’s growth towards her final bang. The final explosion takes place after she visits a fortune-teller, who makes her dizzy with hope by having ‘sentenced her to life’. In this moment of glory, with her eyes glistening ‘like the dying sun’, Macabéa steps off a curb and gets hit by a Mercedes ‘enormous as an ocean liner’. In Macabéa’s final moments, the grand macro inhabits the bright, wretched micro of her body.

Explosions harness a potential to move between the macro and the micro — a conceptual zoom that connects the events on the lifeline of the individual to those on the lifeline of the universe. Aptly for Macabéa, the sensation of this compression — which takes the atoms of the body back to the moment of the Big Bang, the explosion that provided the energy for the expanding known Universe — is akin to life flashing before one’s eyes. By breaking the ground of existence, explosions place an orange blaze into the normally greyed line of our writing — a fleeting heat amongst concrete solids. They destroy the old at the same time as creating ground for the new — a turning point that acts as a punctuative hook. Whenever something happens to me now that has an energy above the decibel level of my normal day-to-day, I think to myself: (explosion).

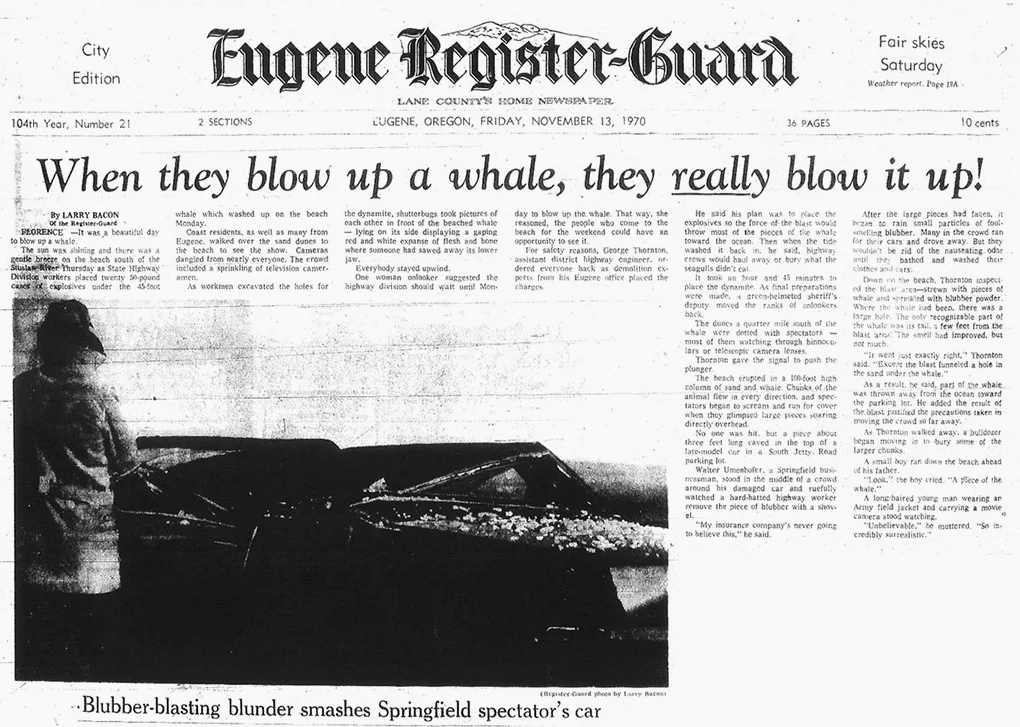

Cloudy with a chance of blubber. An exploded whale in Florence, Oregon, 1970

Fragment 2

A human-size stone with a small number of inversions.

Explosions provide interactive points between the ancient and the contemporary. They shudder at their edges, testing them against the words ‘past’ and ‘future’. This facet of their being is emphasised by the phenomenon of exploding whales, recorded in urban legends and viral videos [Bang: animal, man-made, mythology]. Whales are lent a certain mythology due to their biblical connotations, as well as their presence in folklore and stories about witchcraft, in which beached whales are seen as either offerings or omens. Beached whales are an apocalyptic image, an unreadable harbinger due to their seeming randomness, the largest mammals on earth removed from their context. Once beached, whales can spontaneously explode due to a natural build up of methane in their stomachs, or as a result of human attempts at disposal using dynamite. The most famous example of the latter happened in 1970 in Florence, Oregon, USA. A whale was blown up in an effort to dispose of it; however, this unexpectedly resulted in blubber raining down across an 800ft radius.

The natural explosion of a whale stomach is a sudden spurt of rarely seen organic matter, a rupture in the barrier between internal and external. This explosion confirms the fact of their death, yet also creates a creature active in the present. The potential of this explosion bubbles on their murky hides as people stand around snapping pictures in the bright sunlight. The possibility of this explosion is itself a rupture, disrupting the image of the beach as a family destination and comfortable site of leisure. In postmodern town-planning renders, the beach sits at the edge of skyscrapers. Included in this scene, the heightened viscerality of the exploding whale is a weird thing which brings human progression into focus. The exploding whale is not meant to be there, nor is it meant to explode and make a mess of polished developments. Explosions hang strange in the present, and have the potential to be stranger still if they persist in the slick of the near future, as we exceed our capability to remember everything and our point of origin moves completely out-of-sight, leaving behind only a handful of archaic reference points.

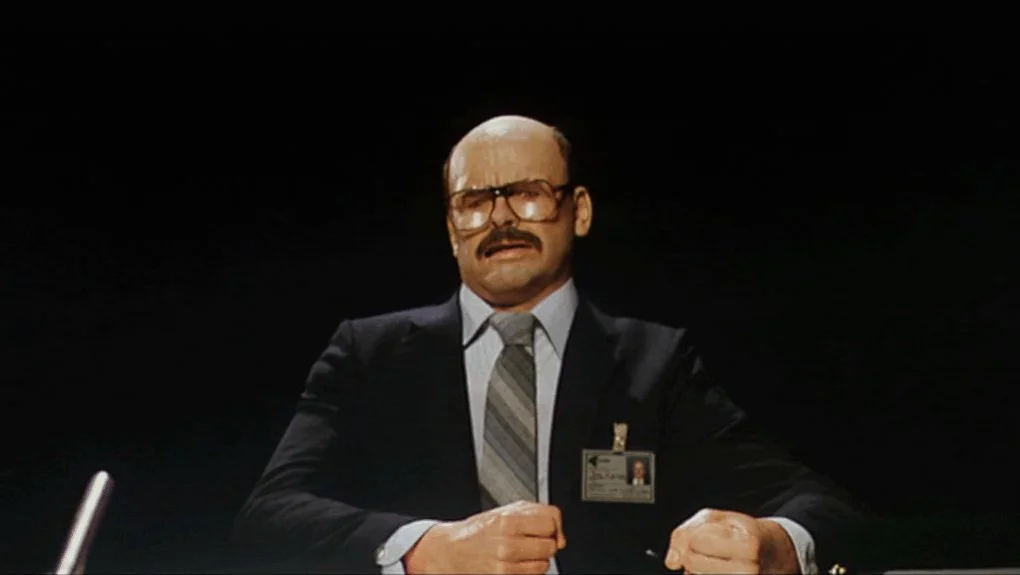

Seconds away from a more literal case of ‘exploding head syndrome’, in David Cronenberg’s 1981 film, Scanners

Fragment 3

A piece of sandstone the length of a forearm, some areas freshly carved.

Despite the fact of a necessary catalyst, a defining characteristic of explosions is their suddenness. Their instantaneous nature, which unnaturally accelerates an object or scene from one state to another, simulates objectification, as they appear at the full height of their power in a space rendered almost blank by contrast. Circulated still photographs of explosions reflect this object-effect, and it is also akin to inserting or losing a frame in a reel of film. The shock of this moment performs a cut, creating an image that can be removed and carried elsewhere. This rogue frame can recur without warning in states of panic, or flare up in reverie hours after inner explosions have softly slipped like silt to the edges of the body.

The sudden jolt of the explosion effects the sense of known reality, as the subject is thrown momentarily out of place and time. This is given image in the body being thrown to another place on the ground by the shockwave, and is stressed further in the phenomenon of ‘exploding head syndrome’, discussed since the 1800s [Bodily: conspiracy, heat, light, pseudo-science, sonic]. Individuals with this condition report experiencing explosive sensations at moments of sleep and waking: for example, an intense heat creeping over the body, seeing flashes of light, or hearing sudden loud noises. One researcher has described the condition as the ‘sensory discharges’ of the patient. The noises are often described as happening right next to the ear: excesses that leak out and explode a few inches away on the soft landscape of the pillow. It has been posited that the condition is a result of stress and anxiety. As such, these experiences, in which all of the body’s auditory neurons fire at once, can be thought of as the subconscious efforts of a body unable to cope within its own skin to go beyond the limits of the epidermis — a body taking up the suddenness of the explosion as a method to try and escape. The jarring nature of these experiences has resulted in some individuals giving explanations of government conspiracies to access their brains using ‘directed energy weapons’ or alien abduction. In the latter experience a segment of time is lost, seeming to provide an opening in the fabric of reality.

The sudden ‘split-shift’ of explosions generates a seeming window of opportunity for the new. Due to the fleeting and urgent nature of explosions, in their aftermath a sense of loss provokes an urge to remember, to interrogate, in collusion with a cold rush of chance that occurs as the space rendered almost blank refills. In cities, time has been reduced to quick seconds due the temporal alterations of technology and hyperactive focus on productivity. As a result of their suddenness, and ‘rogue frames’, explosions can potentially provide a framework for being able to work within this landscape of quickness, to gain a foothold for imminence without slipping, and either put ‘a spanner in the works’ or create gaps for chance.

Chantal Akerman’s 1968 short film, Saute Ma Ville (Blow Up My Town)

Fragment 4

Whitish brown in colour, the same size and weight as a bag of sugar.

Explosions are declarations of a desire to begin again from scratch. Enticingly, they offer the possibility of obliterating everything with a single decision — a means to immediately remove the foul-tasting laws and structures that enable the continuation of oppressive ideologies. This desire is charged with a slipstream of euphoria: the feeling of push me too far, and I will destroy everything, the status quo included, even if this means destroying myself. A retributive spontaneous combustion. However illusory this possibility, there is a thrill to be gained by gripping this unquantifiable danger.

In Chantal Akerman’s 1968 film, Saute Ma Ville (Blow Up My Town) [Bang: anti-authoritarian, girlish, liberating, sonic, symbol-shattering], this desire is depicted in action. This was Akerman’s first artist film; she is the only character, an eighteen-year-old girl-protagonist who explodes her Parisian apartment. The majority of the film is set in Akerman’s kitchen. She carries out tasks in quick succession with a pragmatism underscored by mania: gulping red wine and spaghetti; cleaning the floor with a swill of water; throwing the cat out of the window; polishing her shoes then continuing to polish her bare skin up to her knees; and taping up the door to her apartment. Anticipation colours Akerman’s performance of these household rituals — she may be thought of as the fizzing spark. These tasks symbolise the prescription of the individual to live by set domestic and social rules. Akerman returns to the original etymology of ‘explosion’, from early seventeenth century Latin, explosio(n-), meaning ‘scornful rejection’, critiquing these confining laws and expressing a will to see the individual liberated. This sense of imminent freedom is accentuated by Akerman’s disembodied voice, which sings a joyous fever. This vocal score floats above the frames as if the voice inside her head, a litany of dum’s and di’s, and cartoonic gloats of ‘Bang! Bang!’ which collude with other noises: for example, the tick tock of a clock heard when she opens a cupboard and which promptly ends once it is slammed shut.

The film closes with Ackerman turning the gas hob on and macabrely swooning over the cooker, holding a bunch of flowers. Rather than an explosion filling the screen, it shocks black — we are witnesses to the explosion through sound alone. As the explosion subsides, Akerman’s voice starts up again, the timbre of her prior tune heard afresh, affirmed in its nihilistic glee — everything is constructed, therefore we can explode it repeatedly. Akerman presents a cycle of accumulation, explosion and freedom, apparently achieving a new blank space within the filmic reality. There is no rubble, no aftermath, only her subconscious survives — an acousmatic cockroach. The concept of destroying everything to start again feels increasingly detached from our current reality, a thing built upon systems of digital recording, a trail of the mundane and the significant ever-growing in volume. Politically, we should work inside the thing and be permanently imminent as if a fuse, and allow this fantasy of the explosion to hover overhead as our talisman. As distaste grows, the fantasy to begin again does too; explosions provide a ready muse to keep our retinas permanently alight. Even if it is impossible to begin again entirely from scratch, conventions can still be blown to smithereens.

Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, released in 1970

Fragment 5

A piece of fool’s gold, malleable, can be compressed like cheap white bread.

The temporal stretch of explosions is illustrated in two sequences in Michelangelo Antonioni’s, Zabriskie Point, a film set in the USA in the late 1960s. The first sequence [Bang: liberating, multiplied, pleasure] takes place when the female protagonist, Daria, and her counterpart, the maverick revolutionary, Mark, venture into the ancient riverbeds of Death Valley to consummate their adventure. Their coupling spawns numerous other pairings who appear copulating in the dust. Their sex is textured by cuts between their bodies and these associated figures. This birthing of multiples expresses the stretching sensation found in the explosion and this sensorial space (as well as being a political nod to the counterculture of free love). The sequence closes with an aerial shot of the couples strewn across the dunes, as if they are the fragments that have been flung from the explosion of Daria and Mark.

The second sequence [Bloom: anti-authoritarian, multiplied, symbol-shattering] closes the film — it lasts for several minutes. The subject of the explosion is a shiny, futuristic house perched on a crag of red rock, in addition to the authorities contained within it. This setting nods to the conflation of the desert with luxury, by way of explosions to find oil and gold, and its expanse of untouched land and air (the house is part of a development built to cope with the town’s burgeoning population). The explosion is witnessed through the eyes of Daria; we presume it is her fantasy, an expression of her feelings of retribution, revolution and grief, as Mark has recently been killed at the hands of the police. A premonitory flutter of the ensuing explosion is spliced-in seconds before as if a piece of dust on Daria’s eyelash. The fantasy forms, we see her blink, and then she looks into the distance: the explosion commences. The first moment of the blast is repeated over ten times from multiple angles, the camera moving closer with each shot so that we can conspiratorially enjoy every rupture and ricochet of the destruction. Following this reliving, the camera sweeps to the right and falls into a slow-motion reverie of exploding tableaux of Americana — fridges, television sets, sliced bread — rendered with a painterly palette of red, white and blue.

Further to their explosive forms, the duration of these scenes is far longer than filmic convention would have us expect, playing with durational affect and expressing the sensation of explosive stretch. An explosion demands the eyes of its witnesses, creating a subject rooted in an awareness of their own body, pulled outwards from their eyes to the explosion in front of them. This holds some similarity to the feeling of not being able to look away from a car crash, yet it is amplified by additional layers of propulsion due to the colossal scale, abnormality, and soft, organic, beauty of explosions. Time appears stretched as the presence within a single moment is prolonged; in these moments, all that is present is the body of the witness and the body of the explosion. As such, what we are left with is an internal-to-internal relation — we know the feeling of being in our body, and we can see and feel connected to the bare form of the explosion. This is a relationship built on fascination in the archaic sense, in which objects are potent in their non-verbal communication of all the things that they have seen across time. The eye looks for answers but none are to be found, thus it is left roving in a reinvigorated relationship with material. This engendering of fascination by explosions — in which, pertinently, the body is extremely present — renews a relationship with material, and thus can potentially take a thing from semblance to solid. Further to this, in opposition to the reduction of attention spans and flitting information patterns devoid of absorption, explosions potentially bring forth a framework for a reinvigoration of engagement, based on the mode of fascination.

Explosions shuffle the normative structure of time; they shift us from our state of prescript devotion to seconds and minutes. There is the ripping of the body and the eyes to an inhabitation of the single moment, followed by a feeling of all sense of time being lost. In the actual bloom explosion, this slowing down is expressed in the hanging seconds between the flash, the bang, the aftershock. Abstracted, this stretch is limitless — as the gaze is drawn upward it can continue on and on into the sky. Within this stretched space, an explosion can offer a different zone that is both potentially limitless and contained inside the explosion membrane. If inhabited, potentially other work can be carried out inside this temporal space, created through a focus on the micro that demands the self away from the swamp of the macro and into the freedom of the open air.

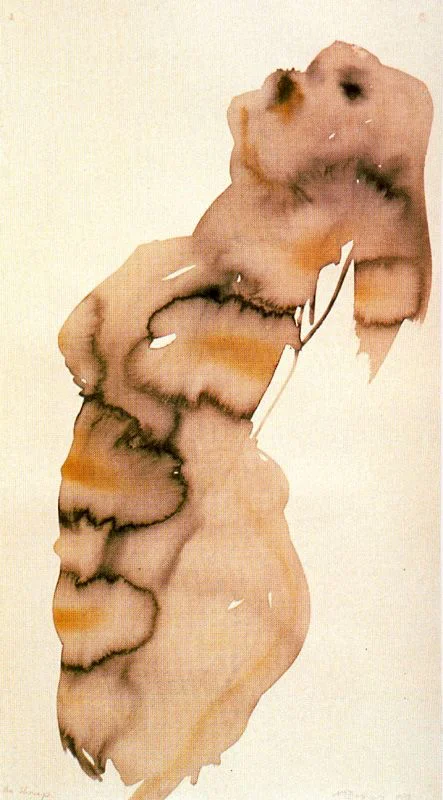

Marlene Dumas’ watercolour painting, The Shrimp

Fragment 6

Swallowable in size, pilose, lightweight.

When thinking about how explosions can offer alternative temporalities and revivify materiality, there is an explosion readily at our fingertips — an explosion of pleasure. In this usage, ‘explosion’ vibrates; an image applied to the skin atop hedonic hotspots, which upon sinking in, sharpens the details of sensations. The temporal framework that provides pleasure’s foundation mirrors that of an explosion: escalation towards a burst of energy followed by a rapid scattering of heat. Aside from the warm centres and circular dispersions of climaxes, during the physical pleasure of sex as event, time can stretch like a tendon in time with the body that arouses it — an elongated inhabitation of the bloom column. When the body gives in to losing its beginning and end, the normative line of time changes condition, becoming slack. This is not only a desire for total hedonism in the face of over-stimulus — a belief in pleasure as anti-authoritarian, or a retreat to the sense of touch — it is a turn to pleasure as a pragmatic means to push against, and widen the increments of, recorded time, wriggling around inside them in order to dilute time’s fidelity to labour.

Further to this, interior explosions effect a renewal of the subject. New energy sweeps through dormant cells, performing the oscillation between death and birth found within explosions’ fiery membranes, and engendering an awareness of the physical body down to a microscopic level. Pleasure offers a means to clamber back into the body that has been muffled and made sedentary by screen-based labour. It is potentially one way to feel a new beginning (however simulative) in a time of being permanently ‘on record’. We are living in a time when things are actively being emptied of their contents due to increases in screen-based viewing; mainstream images of pleasure also continue to smack desire sterile, in aesthetics devoid of texture and visceral delight (capitalism has increasingly commodified our desires and caused our desires to be commodities). Pleasure works within the conditions that we already exist within, providing its own ‘automatic shift’ into a different temporal space and offering a focused engagement with materiality. The feeling that you are outside of scheduled time, allowed by a daily, bodily explosion, is not something to be dismissed. It is another way to push our bodies, not by technological advancement but by material potency against the implosion of nullification: pushing energy outward while simultaneously keeping it within. If the body is being drained, perhaps it can be rebuilt through an accumulation of explosions.

In Marlene Dumas’ watercolour painting, The Shrimp [Bodily: animal, multiplied, pleasure, women], (one half of the couplet The Alien/The Shrimp), explosions are produced inside a grey-blue-washed body minus knees and calves, that has an arched back and upturned face — a visualisation of ecstasy. Yellow centres give way to a gap of skin before seeping into outer rings of dark blue. The process of the drawing is driven by time and material; its form is determined by the movement of the material. Speaking about this work, Dumas notes that ‘you cannot imitate the speed of your gestures’ nor can you imitate a drawing made using such a process, as then ‘it will be very dead’. Dumas’ drawing presents a figure in which life is encased. If we internalise explosions, they can act as fuel for self-made impetus; this is especially true if they are recurrent in our flesh. The multiplicity of the explosions instils a self-birthing sensation, built on chain reaction. A thing that is self-birthing leads to more and more, rather than closing it back down. Explosions sound inside Dumas’ figure’s abdomen and curve along her spine and neck — the multiple orgasm of her inky frontiers.

I have seen the glory and the power of the word.

I have experienced the power of repetition,

the intoxication of rhythmic rhetorical arousal.

— Marlene Dumas, ‘Why Do I Write (About Art)’, Sweet Nothings: Notes and Texts

Following Dumas’ statement, I whisper to myself: explosion, explosion, explosion, explosion, explosion, explosion, explosion.

Imagine a body within which multiple explosions sound, floating up to the limit of our expansion; this edge, a glass wall that when reached deflects us backwards, into a state of implosion. Imagine this figure exploding this demarcation line, before continuing through the debris, and into a new space. It bobs along in the black of the unknown, just as Dumas’ ecstatic hybrid hovers on the page as if the fleck of a single organism in a vast ocean. If we consider ourselves as adrift, tipped out of the impetus of the explosion, the question is: how might we harness the powers of the explosion in this time? How might we seek a different turn of being using our ‘explosive tastes’?

If explosions can effect time and materiality, and stand powerful enough to transcend the screen and speak to our bodies, then they are an emblem worth keeping tucked under our ribs for safekeeping as we move towards the final frontier of expansion.

Jennifer Boyd is a writer based in London. Her research interests include emancipatory sensations, subversive politics, and the materiality of language. She has previously written for SALT magazine and the Center for Contemporary Art, Estonia, and contributed to Either/And at the National Media Museum, Bradford. Her audio-essay and collaborative film on the ‘eerie’ was shown at Goldsmiths, London, and Peninsula Arts, Plymouth, and she recently gave a performance about twisting bodies in two at Even Salon, London.

Dave Gaskarth is a London-based visual artist.